Four years ago, the 600 villagers in Agou Avedje, in the West African nation of Togo, had no latrines and a sanitation problem. Volunteers with the Denver chapter of Engineers Without Borders-USA had offered to help. But before the villagers would accept, they first had to learn to trust the outsiders.

The volunteers had decided to build and sell latrines for $15 each—about 10% of their full cost. The rationale was that people value what they have to pay for more than what they receive for free. For some in the village, even the discounted rate was steep, and they weren’t sure they could trust the outsiders.

For years, the volunteers discovered, Agou Avedje had received largesse from well-meaning philanthropists, Togolese government workers and outside aid organizations. Yet many of those groups stayed briefly and then left and never followed up. This behavior had imprinted on some villagers a low-grade suspicion of volunteers’ long-term intentions.

Countering the villagers’ distrust has required a combination of a good Togolese interpreter, water filters and possibly a video.

Don’t write it, say it

Many of the villagers can’t read, and they distrust written agreements, said Chris Fahlin, the Denver Professionals’ program leader. The solution may be DVDs. A Belgian aid organization had supplied the village with PV cells and a media center with a DVD player in a laptop. The EWB-USA volunteers plan to record video explanations of the project that the villagers can consult whenever it suits them.

Clean water handouts

The volunteers partnered with a handful of organizations. They included Peace Corps volunteers who were already working there, Water for People, and a local Togolese organization called CADO (Centre d’Assistance aux Démunis et Orphelins—Centre for Assistance to the Deprived and Orphaned).

One of the partners suggested that the engineers distribute ceramic water filters to the village’s households. The filters are manufactured in neighboring Ghana as part of the Potters for Peace program. Fahlin initially resisted the idea. “I wanted nothing to do with the ceramic filters,” he told E4C. “I knew that they weren’t a long-term solution.”

In spite of his concerns, Fahlin gave the go-ahead to distribute the filters. He conceded that people are healthier with fewer stomach parasites since using the filters. And, he said, they served as a token of the seriousness of his group’s intentions to work in the community.

How an Eco-San latrine works

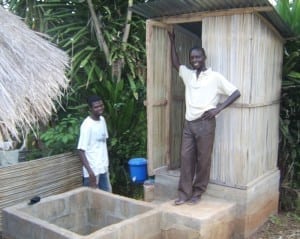

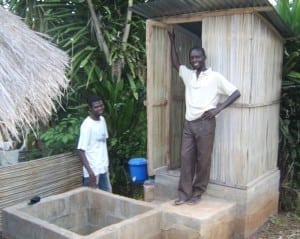

Over the past two years, families in Agou Avedje have bought 23 Eco-San latrines. When each of the village’s 114 families has a latrine—sometime in 2012, if all goes well—the EWB-USA team, with the help of CADO and the Togolese government, plan to expand the program to nine surrounding villages.

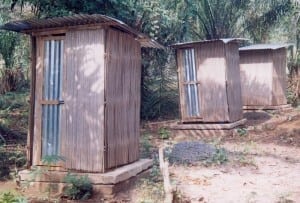

EcoSan latrines have raised bases to keep rainwater from flooding the composted waste. Each has two pits, side by side, with wooden walls and a corrugated metal roof around one of the pits. A mixture of ash and soil is scooped over the waste after each use. The ash mixture reduces odors and moisture and raises the Ph of the resultant compost. When one pit fills, the family moves the wood-walled enclosure to cover the second pit. After the waste has composted for one year, they shovel it out to fertilize their crops. Alternating between the two pits should be a long-term sanitation solution.

Are they being used?

Installing latrines does not guarantee that they’ll be used. As we reported earlier, only about one-fifth of latrines that make compost are used often and correctly, according to a study of 400 communities by UNICEF in 2006. In Agou Avedje, however, all of the 23 families that bought latrines so far are using them and sharing them with their neighbors. The EWB-USA team carried out formal evaluation and found that all of the families report satisfaction with the project and sanitation has improved. The families are also using the compost from the latrines on the field. And, interestingly, snake bites are down, because people are using the latrines instead of walking into the bushes.

How can we help?

Besides the latrines, the EWB-USA team has a short list of projects they’re contemplating for that part of Togo: Internet access, irrigation, and micro-businesses. They could use experts (and newbies, if they have leaders to accompany them) in those fields, as well as videographers and photographers. They could also use more money. To make a donation or for more information, please visit their site.