A new generator that draws power from the difference in salinity between freshwater and saltwater may have the potential to power small cities, researchers say.

It has not yet left the lab, but the working model, and the concept, suggest that the generator could be cheap, durable, simple and leave a small environmental footprint. It could be a fit for developing countries, Yi Cui, an associate professor at Stanford University who is leading development of the device, told E4C.

But first, Cui’s team has to find a cheaper material for one of the generator’s electrodes.

This graphic explains how the device generates electricity, clockwise from the upper left. Two electrodes are immersed in freshwater. The purple and orange dots represent positively and negatively charged ions, respectively. In step one, a small electric current charges the battery, pulling ions out of the electrodes and into the water. In step two, the freshwater drains and saltwater flows in. Note the much higher number of charged ions in the saltwater. Step three, the battery discharges its electricity for use, draining its stored energy. Ions return to the electrodes. In step four, the seawater flows out, and freshwater flows in to complete the cycle. Image courtesy of Yi Cui, Stanford University

How it works

The device is a battery with two electrodes immersed in water. It charges at low voltage in freshwater. The freshwater flows out and saltwater flows in. Then it discharges at higher voltage in saltwater.

“That means you gain energy. You get more energy than you put in,” Cui says. The key, he points out, is to exchange the electrolyte–the water in the battery.

In practice, the device would sit near the convergence of an ocean or saltwater lake with a source of freshwater. A river or, Cui speculates, rainwater runoff or even treated sewage might suffice.

With a flow of 50 cubic meters of freshwater per second, a power plant based on this concept could generate 100MW, enough to power 100,000 US households, Cui says. The device would not contaminate the water, and its only emission would be the mixture of salt and freshwater.

Something cheaper than silver

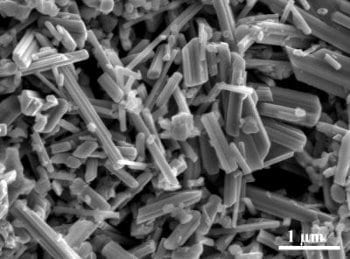

Cui’s team made the positive electrode from manganese dioxide nanorods. The material is more efficient and environmentally benign than other materials, Cui says. It increases the electrode’s surface area to improve its interaction with the sodium ions.

For the negative electrode, the researchers used silver. That, Cui realizes, is too expensive. “We’re searching for another electrode to replace this one. That’s the only high-cost component. Everything could be low cost,” he says.

What could that cost be? “It’s too early to guess,” Cui says. “From the materials, I think it’s a very low cost. It can be practical.”