It was perfect timing: I received an email asking for architects and engineers to volunteer in Haiti, the trip would leave in three days, and I happened to have the next two weeks free.

I jumped at the opportunity. I set up a Facebook group to help raise money for the trip and met friends in Manhattan to collect donations of medical supplies and construction tools. I made sure to pack the essentials: tent and sleeping bag, hardhat, caution tape, high powered flashlight, ATC-20 forms (in French or Creole), and a clip board. I also needed spray paint, but I could buy it in Haiti. I intended to donate these items at the end of my stay.

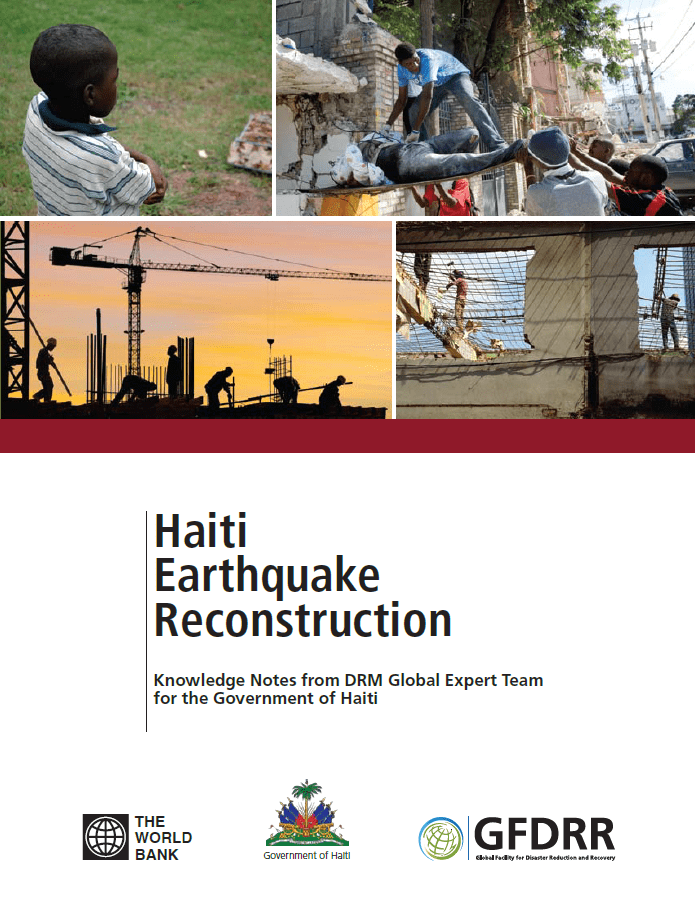

My team, three water and sanitation engineers, a firefighter, a medical student, a structural engineer, and myself, an architect, arrived in Port-au-Prince and was greeted by members of the National Organization for the Advancement of Haitians (NOAH). NOAH and Mercy Corps took on the responsibility of placing us in the field where we were most needed. Tom Sullivan, the structural engineer, and I were asked to relocate to Petit-Goâve, a small town three hours west of Port-au-Prince.

Petit-Goâve’s structures had not been assessed yet in any comprehensive manner. So, upon meeting with the mayor, we were asked to review the town’s civic structures first, followed by schools, then on to privately owned properties. I preferred to assess each building, street by street, in a methodical, unbiased strategy. However, in an effort foster a relationship with the mayor and his staff, we accepted his assignment.

Our work in Petit-Goâve proved to be very productive but also had its share of hang ups. At first, we were happy to work with the local government. Many of the NGOs seemed distant by shuttling around in their SUV’s and making decisions for the Haitian people without consulting them. Tom and I, on the other hand, were working directly with the people. This created problems, however, when we began to assess private properties. There is a clear cultural mistrust of the government in Haiti. And our association with them (we were conducting assessments with the city engineer) often prevented us from being permitted onto private property. I would recommend to groups heading down there that they will be most productive if they can find a way coordinate with the local government but clearly separate themselves as independent.

Another problem that we encountered was the use of colors to mark buildings for safe, semi-dangerous, and dangerous. Because many of these buildings have not been assessed in the two months since the quake, the community is not anxious to hear if a structure is dangerous or not, but whether it can be rebuilt. As a result, our assessments also included recommendations for structural improvements or complete demolition. It is important to be prepared to make such decisions, so take your time reviewing the entire structure. Decisions like these can be overwhelming – but just keep in mind that your opinion is extremely valuable (and more informed than that of most of the builders there).

One of the final hurdles that we encountered was the stark reality that many of the buildings that need to come down are simply too big to demolish safely. Neither the Haitian people, nor the UN or the serving military have the equipment needed to take down some of these structures. This problem is still not solved… If you know any organizations that can volunteer to take down these structures, their expertise is extremely needed.

Upon my return to the States, I have been consolidating all of our reports, notes, sketches and photos into a comprehensive report to hand of the the next group of engineers. The final version will be available on E4C’s beta site after a reorganization of the site’s layout that is underway now. Please check back for updates.