An E4C member asked for a device to help a child with cerebral palsy in Peru spend more time outdoors. The community responded with a handful of ideas. After learning more about the cultural context of the project, however, Kaleen Canevari decided to shelve it. This is an example of a lesson learned early before building something has unforeseen consequences.

Before beginning her doctorate education in biomedical engineering, Canevari traveled to Phiry, Peru this summer to volunteer with the organization Awamaki, which supports Quechua women in their trades as weavers.

Phiry is a village perched 9000 feet above sea level in Peru’s Andes, near Ollantaytambo, the city tourists know as the head of the Inca Trail. The boy, Alex, is 13 years old and lives with his mother and grandmother. They have to leave him home alone during the day. He cannot walk and he cannot speak. “But he lights up and squeals when you walk in the room,” Canevari says. He enjoys the outdoors and watching birds and animals in the town.

E4C responds

If he had a crib of some kind, Alex may be able to spend more time outside, Canevari thought. She posed the problem to E4C and asked for suggestions. Our community responded with ideas for an enclosed wheel chair, a modified walker and an electric tricycle.

As she spent more time in the community and spoke with a social worker who handled Alex’s case, Calevari realized that a crib or chair might be a danger to the boy. A semi-enclosed device could lull his caretakers into believing that he would be safe outside, exposed to the elements for long periods.

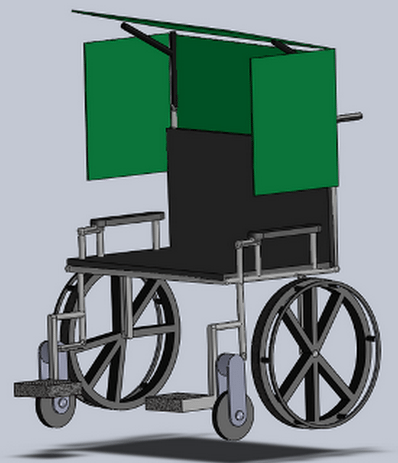

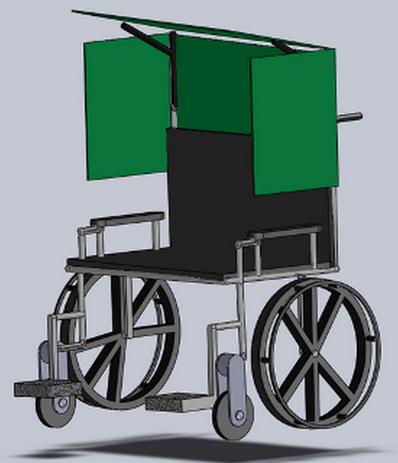

This rendering depicts the chair design that Kaleen Canevari and the E4C community considered for a boy with cerebral palsy

“We didn’t know that we could build something and it would be used inappropriately,” Calevari says. Not building the chair seemed like the best route through those circumstances.

“One of the subjects that came up is, What is normal for Peruvian people in their culture and what is normal for us? We noticed that parents let their kids run around the town and sometimes lock them up in the house when they leave.”

In the end, Calevari wondered if she was trying to change a situation that she and her team were alone in perceiving as a problem. She forwarded E4C’s ideas on to Awamaki to file for possible use in the future and moved on to other projects.

This rendering depicts the chair design that Kaleen Canevari and the E4C community considered for a boy with cerebral palsy. Image credit: behance.net

A rail, a wheelchair and a floor

Among those, she and a visiting carpenter installed a rail on Alex’s bed. He had dislocated one of his hips when he fell out of bed years earlier.

For another project, the team improved an elderly lady’s new, donated wheelchair. The chair had a rugged steel frame supporting an affixed plastic lawn chair. Phiry’s cobblestone streets made for a bumpy ride, and the lady, Nati, was worried about slipping from the chair. The volunteer team fitted it with an improvised seatbelt and a raised wooden foot rest to increase Nati’s stability.

The volunteers also installed a floor in her dirt-floored, one-room home. Cement left over from an earlier project would have worked, except that Nati lives on the ground. Her legs are paralyzed, and for 40 years, she has pulled herself along the floor to move around her home. Cement would be too cold. Instead, the volunteers decided on mud bricks, which is more insulative than cement and warmer to the touch. They made the bricks by hand, working with Nati’s nephew and his children. “A five-year-old and an eight-year-old were teaching us to make mud bricks,” Calevari says.

Lessons learned

For Calevari, deciding not to make the chair for Alex was a lesson in cultural understanding and communication. “I would definitely have to understand what is normal for that particular culture before I do anything. Understand what they do now and why, and what they would do after the project is implemented and why,” Calevari says. “We take so many things for granted and make so many assumptions. Groups swoop in and try to help the people, but what do the people want? Maybe that’s working well for them and they don’t want to change it. You need to have a relationship with the community.”