I consider the art of teaching as kind of stage performance; good teaching requires effective physical and vocal communication skills for giving a presentation and smooth spontaneity in front of audiences, delivered with full confidence. Among different academic courses, teaching a laboratory session tends to need preparation and precaution to ensure participants’ learning experience and safety. However, the complexity of teaching a laboratory class outside of the usual classroom setting does involve uncertainties that may not have been considered before. I am not an actor, but it may be like performing on a completely different stage without a dry run. Imagine such a nightmare! As an invited instructor at Kisimiri Secondary School for A-level chemistry teachers in the regions of Arusha and Moshi, Tanzania, I had the opportunity to avoid that nightmare and practice the art of stage performance for a week-long electrochemistry workshop through the use of two common items: bananas and nails.

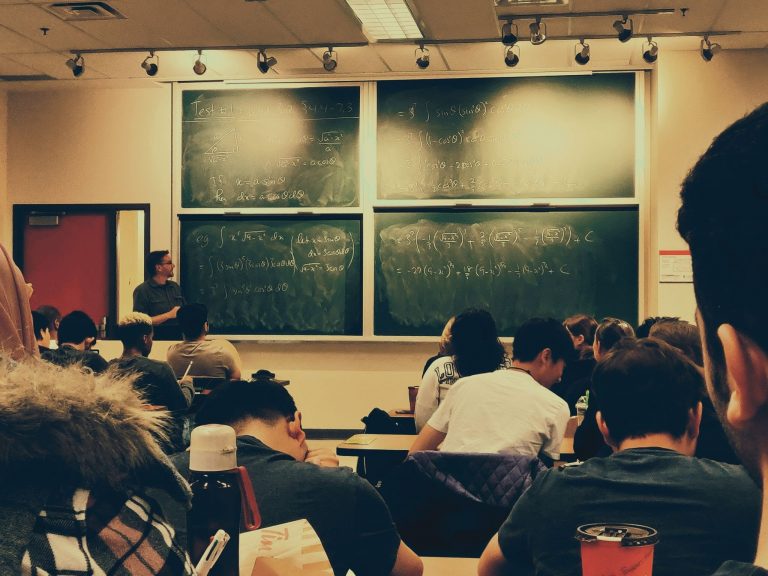

In designing the workshop, I was inspired to deliver a teaching program that would be easily applicable to class settings of the participating teachers. Soon, I was able to figure out that a necessary condition to achieve such ambition was to have a fine balance between teacher-centered and student-centered learning activities. In order words, the program requires diverse teaching methods including a lecture, discussion, and hands-on laboratory session. Here, the first two can be fairly predictable and prepared without knowing where they are taking place. A simple combination of blackboard and chalk will do the job without having a beam projector and screen. However, preparing a laboratory session in a different country did contain an overwhelming number of unknowns to run chemistry experiments. Taking an international flight with bottles of chemical powder and handful of jumper wires in luggage would have attracted unwanted attention from an airline security officer. Thus, those usual lab materials may not be suitable, despite the certainty of their educational value.

In chemistry lessons, just like in global development engineering, adapting designs to the locally available resources can simplify the process.

The more I tried to prepare for the hands-on laboratory session with the level of perfection I intended, the more concerend I became with the prospect of unexpected situations. It got to the point that I was overlooking the essence of the workshop, which was to deliver an electrochemistry teaching program to the local chemistry teachers such that they can incorporate it their own class setting. Then, I started to embrace the beauty of uncertainties, because those teachers would have a similar issue with applying the workshop materials to their own class if the teaching materials were difficult to prepare. Therefore, instead of using formal laboratory equipment and chemicals, I decided to design a laboratory session that needed only easily obtainable household items such as fruit, nails, and baking soda.

The light itself may not have been the brightest, but the idea of creating the banana battery using local resources seemed to brighten up everyone in the room.

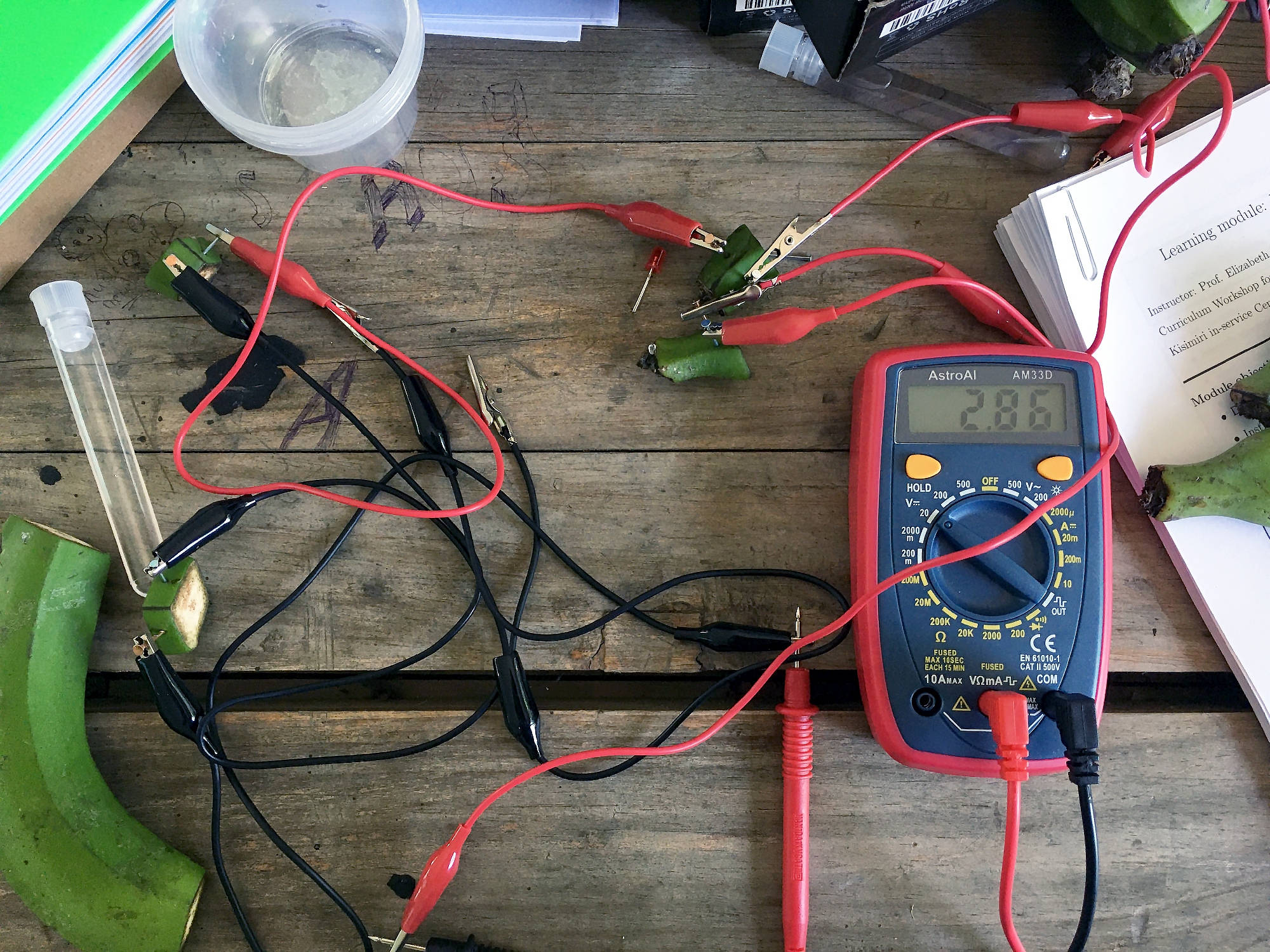

The electrochemistry workshop covered redox reactions and corrosion. Surprisingly, the household items I had collected demonstrated the key ideas of each lecture. For example, by using a fresh banana obtained from a residential kitchen, the concept of electrolyte was explained. Galvanized and copper nails served as electrodes. By combining those electrolytes and electrodes, we had everything needed to make a banana battery. Although I knew theoretically that the banana battery should be able to light an LED, we never know in an actual experiment until we test it. After configuring multiple serial and parallel connections of those banana batteries, we finally saw dim light emitting from the LED. The light itself may not have been the brightest, but the idea of creating the banana battery using local resources seemed to brighten up everyone in the room.

Three banana batteries connected in a serial circuit produce 2.86 V, which is enough voltage to power a light emitting diode. Photo: Sun Hwi Bang

The experience became a mini-lesson for me in the value of adaptation and the necessity of designing with local materials. In chemistry lessons, just like in global development engineering, adapting designs to the locally available resources can simplify the process. In my case, it transformed the untenable prospect of flying with suspicious goods into a fun lesson that the students can repeat themselves using household items. The key to a smooth and engaging teaching performance turned out to be in the use of locally available materials, which included bananas and nails.

About the Author

Sun Hwi was an E4C Research Fellow in 2020, and he is a materials science and engineering Ph.D. candidate at Pennsylvania State University (U.S). He received a Bachelors Degree in engineering from Harvey Mudd College in southern California, and he was actively involved in implementing micro hydroelectric generators in remote communities in Costa Rica. Then he completed a Masters Degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Michigan focusing on adaptive materials and structures. One of his current doctoral research focuses on developing a sustainable composite brick fabrication using locally-accessible materials.