Photos courtesy of Diane Mumararungu

Architects and others involved in designing buildings are often disconnected from the finished product of their work. For good and practical reasons they do not use the buildings and spaces they create in paper and pixels. That necessary state of separation can lead architects to commit the same mistakes repeatedly. it can also frustrate the users of a space by silencing their voices and diminishing their agency.

The purpose of design should not be limited to satisfying users’ needs. Design should also improve health and wellbeing, uplift the values of building owners and use resources effectively. Those metrics may be hard to scrutinze while a structure is still just pixels on a screen or under construction. But once the doors have opened and a place is occupied, one of the tools architects can use to appraise the success of their design is a post-occupancy evaluation (POE).

POE is the process of assessing the performance and effectiveness of the built environment by obtaining feedback from its real-world daily use.

Design should improve health and wellbeing, uplift the values of building owners and use resources effectively.

Research advises that the best way an architect can meet a clients’ needs is by eliminating disparities between the intended (or projected) performance and the actual performance of a design. POEs can close the gap between the design and the day-to-day use of a space.

Read More: Post Occupancy Energy and Environmental Quality – Monitoring & Evaluation, pg. 40 / 2023 Impact Projects Report

POE can dial in a building’s performance. Performance of the built environment is paramount, and probably more important now than ever before. Buildings and construction account for 30 percent of total worldwide energy consumption and 27 percent of total global energy emissions. Attaining sustainable energy performance and reducing carbon footprints, particularly those emitted by building operations, has become a worldwide priority. Buildings with high performance optimize their operational costs, energy use, water use, and, most importantly, they meet the needs of their users.

Bridging performance gaps using POE

POE has its origins in the United Kingdom in the aftermath of World War II [3]. In the 1960s, POE was used to comprehend human behavior and building design. The impact of POEs conducted in this period is reflected in the introduction of environmental design research afterward.

Researchers such as the architect Chris Watson, who wrote a review of building quality using POE in 2003, consider the tool a means of continuous knowledge accumulation used to uncover what works and what does not in buildings.

“Post occupancy evaluation provides a systematic way of learning from the successes and mistakes of previous buildings. It then offers that information in a timely and appropriate way to improve future buildings and to account for design quality of educational buildings,” Watson writes.

For users, POE is empowering. It acts as a platform for sharing thoughts, praise and complaints about the building. For architects and designers, POE enables more holistic understanding of the building’s users. Through POE, designers can firmly grasp concepts that were formerly locked in conjecture. A user’s actual, real-world behavior, for example, becomes clear. Technical and social issues, unforeseen circumstances and many other previously unscrutinized problems are finally identified through gathering lessons learned.

POE elevates a building’s success, becoming a linchpin in the communication between designers, users and project owners.

POE allows designers to go back to what they have planned and what they have built. In POE the following aspects are examined:

- Space planning

- Resource consumption

- Embodied carbon

- Indoor air quality

- User comfort

- Satisfaction

- Inclusivity

- Aesthetic

- Privacy

- Wayfinding

- Design outcomes

- Maintenance and occupation costs

POE highlights the impacts of design on outcomes that may not appear to be closely related to design. For example, POE can reveal the impact that a hospital’s design has on health and recovery rates of patients. Or POE can quantify the impact of housing design on depression rates, or school design on test performance, or office design on productivity and satisfaction in the workplace.

Techniques used in past POE are as follows:

- Walkthroughs

- Individual surveys

- Focus groups

- Interviews

- Satisfaction surveys and physical measurements

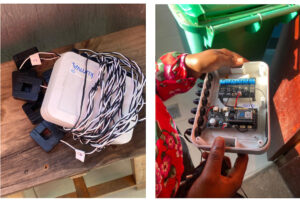

- Deployment of smart devices

- Sensors and actuators

These methods are used to comprehend each users’ point of view, as designers and architects do not often use what they design. POE is used to test whether designers’ predictions have met the expectations of all the stakeholders involved in each project.

In the absence of feedback on a building’s performance, the design and construction industry will unknowingly continue to make the same mistakes, wasting time and money. Users and designers can both benefit from capturing performance data. The data reveals real-world energy performance, helping users know if their buildings are energy efficient and addressing energy consumption issues. Those data can help scale down operational costs. By conducting POE on a building that has been occupied for some time, architects, users and building owners obtain guidelines to achieve the best out of what they have already invested in the building. POE can help match the performance of a building to the users’ needs while affecting future design decisions.

The administration of POE sends a message to building users that the owners and designers care about how they feel about their designs and accommodation. POE elevates a building’s success, becoming a linchpin in the communication between designers, users and project owners.

About the author

Diane Mumararungu is an alum of the Engineering for Change Fellowship Program and an architect based in Rwanda.