Some 75 percent of solar energy kits sold for off-grid use since the early 2000s have stopped working. Entrepreneurs are working to revitalize these much-needed systems.

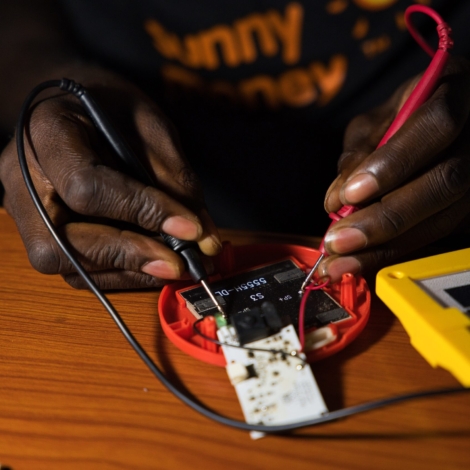

Some nights in Kaputula Village in Zambia, Reuben Musunga repairs solar lights by the light of his own solar light. Batteries are the most likely component to fail in off-grid solar products, according to SolarAid, a non-governmental organization that trains repair techs, including Musunga, through its social enterprise SunnyMoney. Musunga can now replace batteries and repair switches, faulty wiring, and other problems with solar products that stop working.

Each light he repairs chips away at a global stockpile of hundreds of millions of solar products sold since the early 2000s that no longer work.

“We were taught and practiced how to remove and replace a component, soldering, assembly, and most importantly, how to identify a component’s identity when trying to do a replacement,” Musunga said. “Based on the number of products I have been exposed to, I feel confident to handle all the lights that we sell if a customer were to bring them to me for repair.”

The global market for off-grid solar products has surpassed expectations set in the last decade, at a trade volume of $3.8 billion in 2023, according to the World Bank’s “Off-Grid Solar Market Trends Report 2024.” Most of these systems fall under the category of picosolar, which are smaller and more affordable than traditional solar systems and are designed to provide enough electricity to recharge the batteries of low-power-consuming appliances such as mobile phones, e-readers, and LED lights.

While picosolar systems are ideal for off-grid applications in large areas of the Global South, many of the products sold in recent years have stopped working. According to an estimate from SolarAid, 75 percent of solar energy kits sold since the early 2000s (some 250 million units) no longer function as intended. These kits usually include the components needed to build a home solar system, including a panel with mounting hardware, a battery, and a package of lights and appliances. None of the picosolar products that SolarAid included in a study had warranties of more than two years, and many kits and their parts broke within three years, according to their State of Repair report.

Most off-grid solar products are imported into sub-Saharan Africa, which can add a layer of difficulty to the return process. Repairing the products when they break makes sense, and the good news is 90 percent of the distributors of off-grid solar products provide some kind of repair service, according to SolarAid. Repair work faces hurdles, however. Those include sourcing parts and documentation, and a lack of enforced standards for quality and repairability.

Parts and documentation

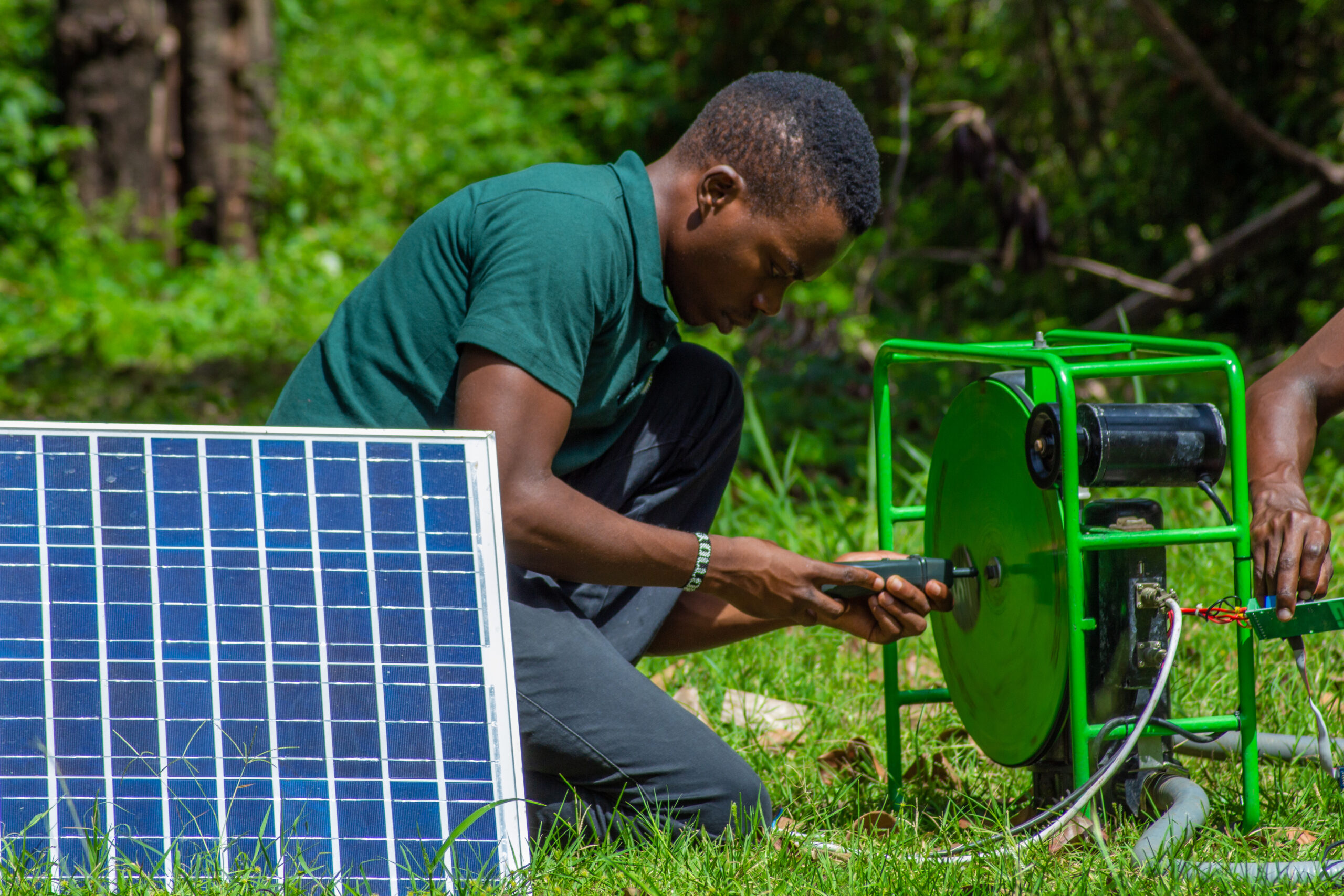

Kinya Kimathi founded Kijani Testing Ltd. to test sustainable products in Kenya. She began offering repair services last year in Kukuma at one of Kijani Testing’s three branches, and has confronted the challenges of solar product repair. She hired four licensed technicians who had a workload of 519 products that they repaired in the first six months of offering the service. Many of the products were solar-powered water pumps. Pumps are in the smallest subset of global solar product sales, according to the World Bank report, but Kijani Testing has a contract with a pump manufacturer, so they see a lot of them.

“The biggest challenge would be accessing spare parts and lack of user manuals to help repair appliances,” Kimathi said. “We are sourcing the spares via manufacturers in China. The process is constantly evolving and we are always learning and improving.”

Sourcing parts could start with the manufacturers. Manufacturers could do more to provide spare parts in the countries where they sell their products, Kimathi said. Likewise, countries could remove tariffs on the importation of parts, as SolarAid recommends in its report.

Repairing small-scale solar systems, such as this solar-powered pump, can keep e-waste out of landfills. Photo: Kijani Testing Ltd.

Repairing small-scale solar systems, such as this solar-powered pump, can keep e-waste out of landfills. Photo: Kijani Testing Ltd.

Manufacturers also play the biggest role in the work to source technical documentation. Documentation, specifically tech spec sheets, is an essential part of the repair ecosystem, as Kimathi refers to the interconnected system of products, regulations, repair services, and waste disposal.

“The issue is there are no manuals for some products and for some they are there, but not in English. End users could have simplified user manuals made available to them,” Kimathi said.

“The biggest challenge would be accessing spare parts and lack of user manuals to help repair appliances. We are sourcing the spares via manufacturers in China.” —Kinya Kimathi, founder, Kijani Testing Ltd.

Documentation could support licensed repair techs and informal repair techs, who are a thriving segment of the repair ecosystem in sub-Saharan Africa. Informal techs are capable, often trained on electronics repair in the local polytechnic institutes and trade schools. They tend to be out of work in the formal sector or between jobs. While the repair sector should work to license and hire informal repair techs to remove the word “informal” from their job titles, a pragmatic view includes them in the mix of people repairing products.

Open source documentation and apps could help. SunnyMoney built a freely available mobile app for repair techs called the Picosolar Repair Guide. SolarAid said the app is a foundation to build on, and calls for collaboration throughout the repair ecosystem to develop open access repair guidance.

Missing standards

Only 27 percent of off-grid solar energy products are quality-verified, the World Bank reports. Poor quality products drag down sales and impede repair work.

Countries are adopting quality standards, but enforcement is mixed. The quality assurance organization VeraSol works with a growing list of countries, now at 20, to help them implement solar product standards in line with those of the International Electrochemical Commission. Verified products are more expensive, however. Financial incentives and consumer awareness campaigns could increase the number of products that meet standards, the World Bank report suggests.

Standards can improve the repair ecosystem, as well.

Repairability by design

Repairability is not a priority for many solar product manufacturers, and some even add a layer of difficulty by making them tamper-proof. A more thoughtful approach to design, and the implementation of product standards, could bake repairability into the solar products.

One idea Kimathi advocates is a public repairability index to steer manufacturers toward more repairable designs. Another idea: since batteries are a key point of failure, make them easy to replace.

“Battery failure rate is quite high and the market is riddled with sub-standard batteries,” Kimathi said.

One of her company’s solutions is a program in the works that would refurbish malfunctioning batteries and use them as spares.

Smart design can also simplify the search for spare parts. Manufacturers could make appliances modular and use standardized components that can be easily replaced when they wear out. Taking the next step, parts could be available locally, rather than requiring technicians to order parts from abroad. The different actors in the broader repair ecosystem could collaborate on a local distribution network to provide parts quickly.

Bringing broken picosolar systems back online

A technician repairs a solar-powered street light. Photo: Kijani Testing Ltd.

The number of solar products that end up in landfills in sub-Saharan Africa can be hard to quantify. Broken solar products accounted for 3 percent of 55,000 metric tons of electronic waste binned in Kenya in 2017, according to research by the UK Department for International Development.

E-waste reduction is important, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. Repairing broken solar products makes ownership more affordable. And affordability is paramount to the 44 percent of the world that lives on less than $6.85 per day. More so for the 700 million people earning less than $2.15 per day.

Research underway now by SolarAid suggests the average cost of a repair is 32 percent of the cost of purchasing a new product. Their research has also found that households are still holding on to nearly all of the products that have broken, and nearly all of those products—91 percent—can be repaired.

“This tells us that people want their products repaired. A broken product should not mean the end of the story,” said Jamie McCloskey, SolarAid’s Director of Programs and Partnerships.

“The off-grid energy sector has historically focused on connection points and the number of people gaining access. But real success means sustained access—ensuring that the service continues long after the first sale,” McCloskey said.

For some, solar products can be lifechanging.

In the last two decades, millions of people around the world have been able to own such things as lights, fans, radios, and televisions for the first time. Solar appliances are broadening the services that schools and clinics provide, and keeping their doors open later. And people are eating better as solar water pumps increase crop yields and refrigerators reduce spoilage.

There are 685 million people in the world who do not have electricity in their homes, and off-grid solar products are probably the lowest cost means of delivering energy to 40 percent of them, the World Bank reports. 1.6 billion people around the world have intermittent grid access, and solar products help during power outages.

Reuben Musunga sees the difference picosolar products have made in Kaputula.

“People are now able to have enough lighting at night, especially in my community,” Reuben Musunga said. “I have supplied most of them with solar lights, and most have stopped using kerosene lamps and candles. They are also saving money they would use regularly to buy batteries for torches.”

This article was first published in the April 2025 edition of Mechanical Engineering Magazine. It is reprinted here with permission. See the original (available to members of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers): Strengthening the Off-Grid Solar Repair Ecosystem.