Shit happens. It is known that international development programs don’t always go as planned, and the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) sector is no exception. Our programs often don’t achieve their stated aims, and sometimes actually cause harm to the intended “beneficiaries.” For example, you might have heard the statistic that up to 70 percent of handpumps installed in Sub-Saharan Africa are no longer working, but a lesser known (and more horrifying) failure of the sector may be accidents where children and the elderly have fallen into, and sometimes drowned in, improperly constructed pit latrines.

WASH researchers and practitioners routinely discuss unintended negative consequences, often informally, over a beer. However, we believe that until a culture of sharing and learning from failures is more widely instilled in our sector, we will continue to make the same mistakes over and over, possibly at the expense of those whom the programs are designed to benefit.

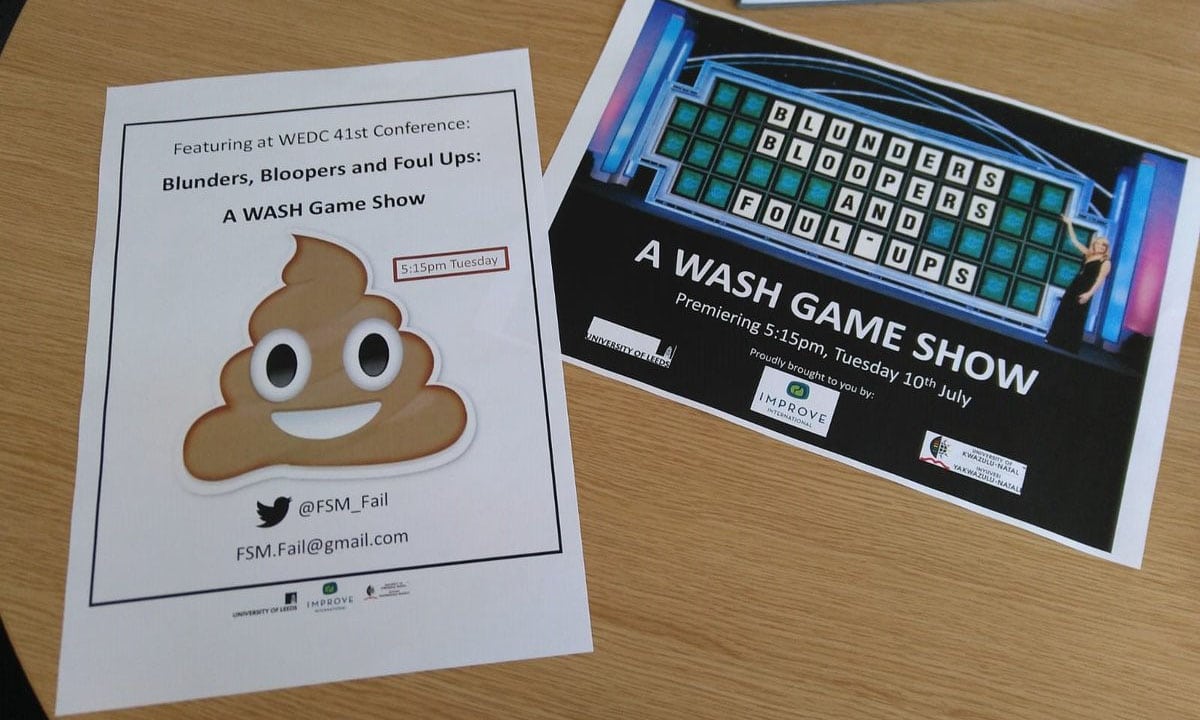

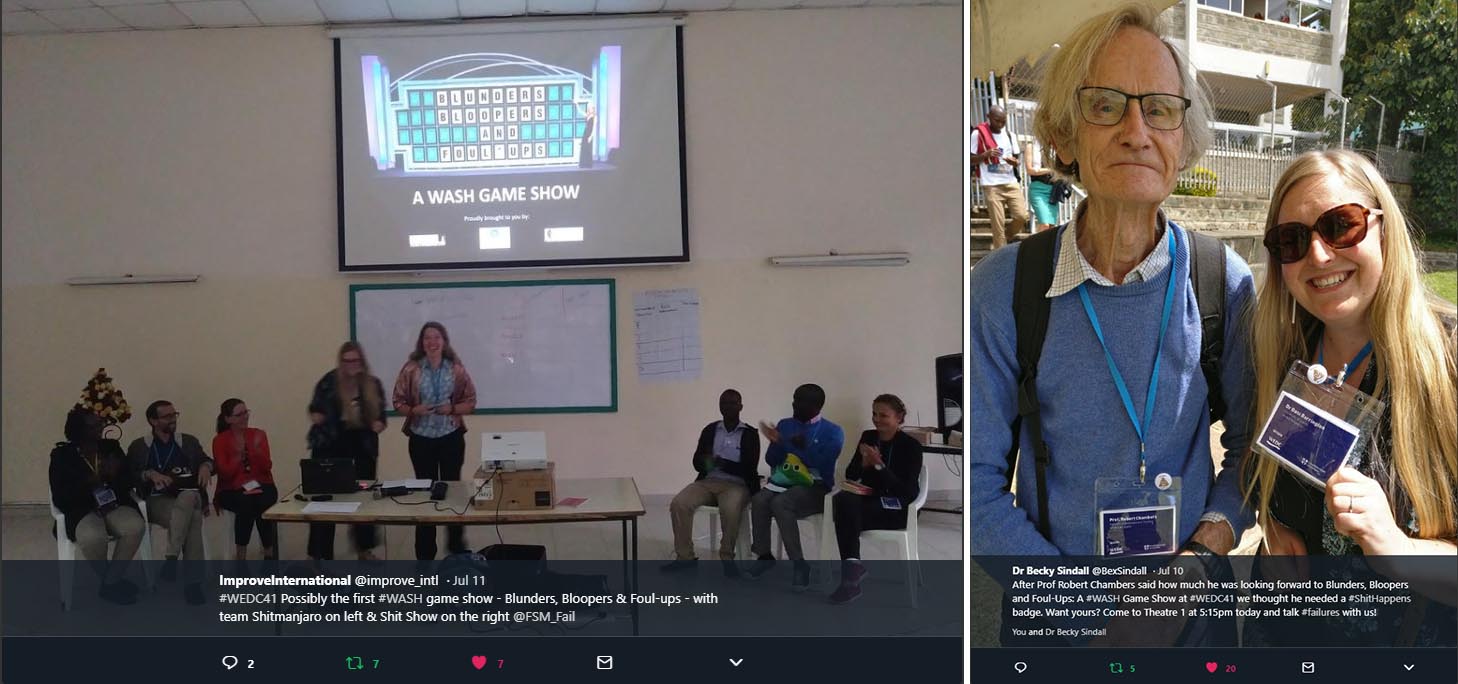

To encourage more open discussion in the WASH sector, we hosted a “failures event” at the recent Water and Engineering Development Centre (WEDC) Conference in Nakuru, Kenya. It began with a funny fails video that had the more than 80 audience members chuckling. Then followed a game show featuring two teams of WASH professionals who had to decide whether failures presented to them were real or fake. Some of the real unintended consequences of WASH programmes presented include:

- Public latrines built by an aid program that were dismantled and used for firewood by community members, as that was considered a greater need than sanitation;

- Women who deliberately blocked household water delivery systems with rocks because they wanted water collection as a legitimate reason to leave the house and socialise with other women;

- The installation of lighting at toilet blocks in a refugee camp to increase safety of women, which led to groups of men using the light to play cards there at night and consequently, making women feel even less safe about using the sanitation facilities.

After using the game show as an icebreaker, we moved onto the serious side of failures. Yes, they can be funny, or inspiring, but they can also have more sinister outcomes. Some of these unintended negative consequences may never be recognised, at least formally, particularly if they are so unintended that they don’t appear in any formal monitoring requirements. To illustrate, we asked the audience to watch this video of a water cannon being used to deter public urination in India:

They then voted on whether they felt the project was a “success” or a “failure.” The vote was split pretty evenly. Some people felt it had been a success because they believed it stopped people openly urinating, whilst others felt it had been a failure, as people would have just moved to urinating openly elsewhere.

The audience assumed that there was a binary distinction: did open urination continue or decrease? But what other consequences should have been considered in assessing success or failure?

The truth is that we don’t know whether the project was a success or failure with regards to public urination. The interesting part was that the audience assumed, when we asked whether the project succeeded or failed, that there was a binary distinction: did open urination continue or decrease? This may have been because the video defined cessation of open urination as the project goal, but what other consequences should have been considered in assessing success or failure?

Were there unintended negative consequences arising from this project that would outweigh positive success factors such as behaviour change? Were people injured from the force of the water cannon? Did people lose their jobs for turning up to work soaking wet or late after having to return home to change? Were people ridiculed to the extent that they felt it negatively impacted their self-esteem?

There is a need in this sector to understand how we can address failure, prevent it, and learn from others without shrouding things in secrecy and shame.

This led to a discussion of times when the WASH professionals in the room had learned a lesson from a programme they worked on not going according to plan. There was a united call for WASH professionals to be “fiercely transparent” in reporting all of our work, and being open to understanding where and how unintended negative consequences have arisen: and learning from those occasions to ensure the same mistakes are not repeated.

We hope that this is just one of many events in the WASH sector where we can begin sharing our failures more openly; our strategy included handing out “Shit Happens” badges, which turned out to be the must-have accessory of the conference, and a talking point for the next three days.

Probably more important than sharing our failures openly, there is a need in this sector to understand better how we can address them, prevent (at least some of) them, and learn from others, without shrouding things in secrecy and shame. We have a few ideas up our sleeves, including an action research project where we will ask WASH professionals to analyze their own data to help us make practical recommendations. For updates, follow us on Twitter @FSM_Fail.

About the Authors

Dani Barrington works on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in low resource contexts. She uses participatory research methods to work at the intersection of technology and society, particularly investigating how appropriate WASH technologies, programs and policy can improve health and well-being outcomes.

Rebecca Sindall is the Operations Manager for the Engineering Field Testing Platform in Durban, South Africa. The platform tests sanitation prototypes in informal settlements and rural households. Her other interests include disaster risk reduction and drowning prevention in LMICs.

Esther Shaylor is a water and sanitation engineer and published researcher with a focus on designing and implementing innovative solutions to WASH challenges in resource poor environments.

Susan Davis is founder and CEO of Improve International and a former Contributing Editor at E4C.