By Mollie Bloudoff-Indelicato and Jessica Pothering

Sustainable development. Environmentally conscious. Responsible business. There are no shortage of buzzwords flying around the private and corporate sectors to convey companies’ strategies “for good.” But a handful of prominent companies have long taken the position that where there is need, there is opportunity, designing and bringing critical products and services to underserved markets. For them, their approach does not have a special name; it is just business as usual.

“We have to be here. If we are not here, someone else will be.” That was Cisco System’s “chief globalization officer” Wim Elfrink, who made the statement when the communications networking giant sent him to Bangalore, India in 2006 to build “Cisco East,” its emerging market headquarters. “You have a billion people here, a billion people in China, 300 million people in Indonesia—all of whom will start consuming and enjoying life. If we don’t understand these economies and cultures, how can we be a global company?”

“We have to be here. If we are not here, someone else will be.” That was Cisco System’s “chief globalization officer” Wim Elfrink, who made the statement when the communications networking giant sent him to Bangalore, India in 2006 to build “Cisco East,” its emerging market headquarters. “You have a billion people here, a billion people in China, 300 million people in Indonesia—all of whom will start consuming and enjoying life. If we don’t understand these economies and cultures, how can we be a global company?”

Not every company takes that point of view. Billions of people live without access to basic services like clean water, sanitation, energy, healthcare, and quality education, because they are unserved by public and private actors alike. But there are examples of others like Cisco that have embraced the idea that serving the underserved is not charity, it is the business of tomorrow.

The following case study highlights examples of this corporate mindset and how it is impacting lives in underserved markets around the world. Below, we profile Cisco Systems, General Electric, and IKEA.

Spotlight: Cisco Systems

When Cisco sent Elfrink to India, his mother-in-law reportedly asked him what he did “to deserve this.” She did not mean it in a good way. At the time, India was a place for American companies to set up a helpdesk or call center, not open a major corporate hub. But that was precisely what Cisco tasked Elfrink with doing.

“They are not just talking about taking products from San Jose and changing them a little. They are looking for new markets. I have not seen another company do this at this level,” Sridhar Mitta, a prominent player in India’s tech industry and founder of social enterprise NextWealth Entrepreneurs, told The Seattle Times in 2008. By then, Cisco had already hired 5000 staff for its Bangalore campus.

Cisco, which is best known for its internet connectivity hardware, like routers, first established a presence in India in 1996. The Bangalore location was then used to support U.S.-based product research and development. Under Elfrink’s leadership, however, India became a base for new product development for both the Indian market and other emerging markets. Today, Cisco East is the company’s second largest research and development team, with more than 11,000 engineers and 1000 global patent filings.

Cisco launched its first product— a mobile backhaul router for mobile network operators—from Cisco East in September 2011. It was designed uniquely for the Indian market, being low-cost relative to other Cisco routers, energy efficient, to accommodate the country’s unreliable power supply, and made to support “legacy 2G networks as well as 4G/LTE networks,” according to a case study on Cisco published by the International Institute of Management Development (IMD). “Such an offering did not exist in the market at the time.” Within 10 months, the router and subsequent iterations sold to 100 customers in 46 countries.

Although it took nearly five years from the time that Elfrink set up shop in India for Cisco East to launch its first product, that product reflected the opportunity Cisco saw in India’s fast evolving telecommunications market. “The market grew [more than] 20 times in just 10 years, from 28.5 million [mobile] subscribers in 2000 to over 621 million in 2010,” the IMD case study notes.

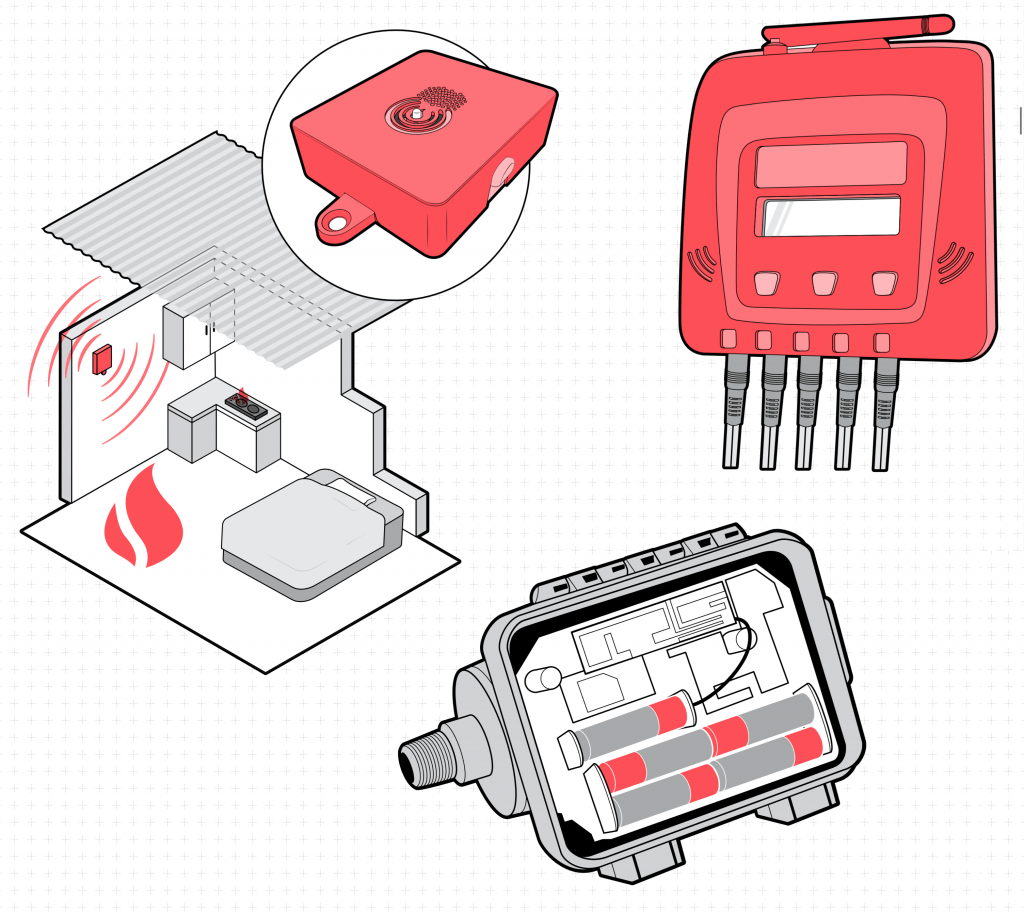

The “Internet of Things” is now comprised of billions of connected devices. Clockwise, from upper right: Nexleaf Analytics’ StoveTrace, SWEETLab’s SweetSense, Lumkani’s networked fire detector.

Cisco may have had a hunch then for where global communication was headed that many of its major Silicon Valley tech peers were only beginning to sense. At an event hosted by the Milken Institute in 2008, a representative of Intel on at panel titled “Are Mobile Devices Replacing the PC?” posed the question “Are we trying to shrink the PC into a phone, or make the phone grow up into a PC?”

Nine years later, anyone can easily see how that panned out. There are now 5.2 billion mobile subscribers worldwide, according to a 2016 Mobility Report from Ericsson. That means that 70 percent of the world’s population has at least one mobile device. Fifty-five percent of all mobile devices in use now are smartphones, and smartphones account for 80 percent of all new devices sold.

In terms of geography, Asia is the fastest growing mobile market in the world, followed by Africa.

And in terms of mobile data and internet services demand, one million new mobile broadband subscribers will be added every day for the next five years. By 2022, mobile broadband will account for more than 90 percent of all mobile subscriptions.

Amid the rise of mobile technology, there is the “Internet of Things” (IoT) domain—a broad category of internet connected devices that includes everything from fitness wearables to agricultural sensors. By 2020, there will be 200 billion IoT devices in use globally, many of which are being used to fill critical knowledge and resource gaps in healthcare, urban planning, agriculture, and natural disaster prediction and response. Some notable examples include Lumkani’s network-connected fire detectors for residents of South Africa’s informal settlements; NexLeaf Analytics’ StoveTrace device, which is trying to illuminate performance and usage patterns for clean cookstoves; and SweetSense, a remote monitoring device used to track usage of water and sanitation infrastructure.

The thread tying these disparate types of devices and their respective applications together is that they all depend on the type of wireless and mobile connectivity that Cisco specializes in.

“Across the world, many people still must confront a number of difficulties from climate change, endemic poverty, and environmental degradation, to the lack of access to quality of education, and communicable disease,” Cisco’s CEO Chuck Robbins said in a company statement. “While these big issues might seem insurmountable, we believe that technology can play a critical role addressing many of these challenges, while creating a host of opportunities.”

Spotlight: GE Energy

Global communication trends may be shaping Cisco’s product development strategy; for other companies, new business lines are being built around needs. Specifically, infrastructural needs.

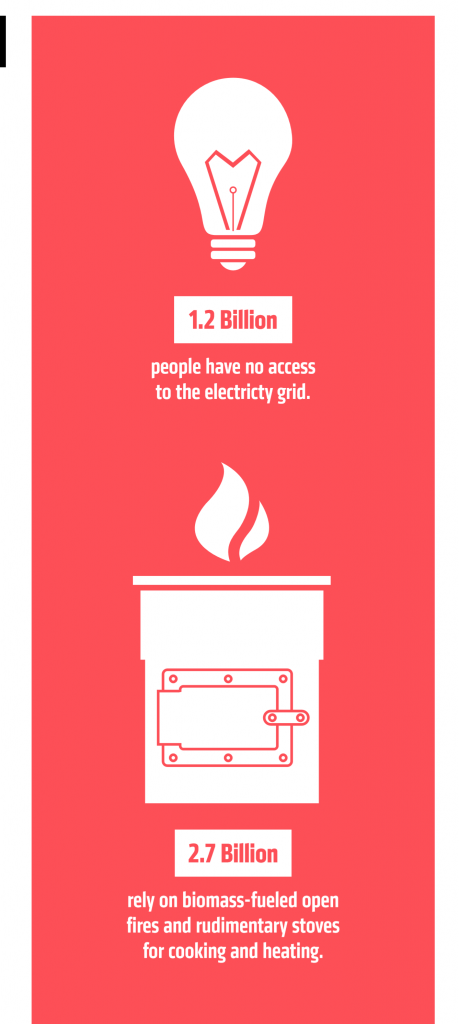

Billions of people lack access to basic, reliable energy infrastructure. Two billion, to be exact, have to contend with intermittent power services daily. Another 1.2 billion—16 percent of the world population—have no access to electricity at all; 95 percent of them are based in sub-Saharan Africa and developing Asia, according to the International Energy Agency.

“For more than half the unconnected population, getting access to the power grid isn’t going to be logistically or economically feasible. But within the challenge of rural electrification lies an opportunity.”

That statement can be found on General Electric’s website. A host of young, off-grid energy companies have embraced that sentiment and are building businesses around it, including notable players like M-KOPA and Off Grid Electric, whose affordable solar lighting products have connected hundreds of thousands of off-grid households to reliable power. Others are more specialized, like FuturePump in Kenya and Proximity Designs in Myanmar, both of which have developed low-cost solar irrigation products for small scale farmers.

Perhaps no company understands the market opportunity of electrification better than General Electric (GE), a $200 billion company whose origin is tied to Thomas Edison, the man who created the first commercially-viable incandescent electric lamp. In 2014, the company published a report on trends it had been monitoring in the distributed power sector—that is, small-scale systems where power is generated for on-site or local use, like home solar systems or community microgrids. Between 2000 and 2012, investment in such systems quintupled from $30 billion to $150 billion while annual generating capacity tripled. “[In 2012], distributed power capacity additions accounted for about 39 percent of total global capacity additions,” the report states. GE’s report also estimates that distributed power capacity will increase from 142-gigawtts in 2012 to 200-gigawatts in 2020, and that investment will increase from $150 billion to $206 billion during that same period.

What’s more, GE’s analysis found that demand for distributed power will increase in advanced and emerging economies alike, but that 90 percent of overall growth in electricity consumption will occur in emerging markets. “These regions represent the greatest growth opportunity for distributed power technologies,” the report states.

GE launched its distributed power business division at the same time that it published that report. Since then, the division has leveraged a host of technologies, from gas engines to wind turbines, to bring power to off-grid areas.

One of its newest (and smallest) solutions launched less than a year ago in the tiny Himilayan village of Rakuru in Northern India. The 700-year-old village is situated in the Karakoram Range at an altitude of nearly 4000 meters. GE partnered with Global Himalayan Expeditions, a socially-minded tourism company, to install three small solar-powered grids for the village’s 70 residents. “The ‘brain’ of the microgrid [is] a charge controller that [determines] when to charge and discharge the batteries, based primarily on the solar panel’s output voltage [and] electricity demand,” a GE case study on the project notes. Power began running into Rakuru for the first time on October 15, 2016.

“The people were hugging each other and dancing,” Shivani Saklani, a member of GE’s Rakuru project team, said in an interview after the project launched. “The experience was so powerful it made me cry.”

GE has committed to working with Global Himalayan Expeditions to install microgrids in 10 Himalyan villages. It has also launched its “renewable hybrid power solution”—a complete solar/diesel/battery-based power system with generating capacities of 15- to 250-kilowatts built into a six-meter container. In January, GE worked with Tata Power to install one of the units in Tayabpur, a village with a population of 1,000 people in the northern Indian state of Bihar. The system includes 12-kilowatt solar panels, a 48-kilowatt battery set, and 15-kilovolt-ampere diesel generator, all of which are managed by a controller, to ensure that the most cost-effective power source is being used at any given time.

Projects like Rakuru and Tayabpur exemplify the potential for distributed power to bring reliable, cost-effective energy access to some of the world’s most remote areas—places where the expansion of centralized grid systems is impractical, if not impossible. But distributed power solutions like GE’s could also help societies of all levels of economic standing hedge against the impacts of climate change.

“As the world grows increasingly interconnected, the infrastructure networks that deliver electricity, gas, and water to our cities have never been more important. They are also more vulnerable to a variety of natural disasters,” GE’s 2014 distributed power report says. It notes that there were 905 natural disasters in 2012: “earthquakes, severe storms, tornados, droughts, and floods, that affected 106 million people and caused economic losses estimated at $160 billion.” One of the most destructive—Hurricane Sandy, which struck the northeastern U.S.—caused $65 billion in damage and left 8.5 million people connected to the region’s central power grids without service for weeks, “disrupting fuel delivery, transportation, communications and other critical systems.”

Spotlight: IKEA Foundation

As the threats and impacts of natural disasters escalate around the world, it is not just systems that get disrupted. “Twice as many people now lose their homes to disaster as in the 1970s, and more people move into harm’s way each year,” a 2014 article from the Guardian reported.

More specifically, 24.2 million people were forced to flee their homes due to natural disasters in 2016, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. The organization’s latest research report observes that most of those affected live in “high-risk environments characterized by low coping capacity, high levels of socio-economic vulnerability, and high exposure to natural and human made hazards,” adding that “low and lower middle-income countries bear the brunt of internal displacement every year.”

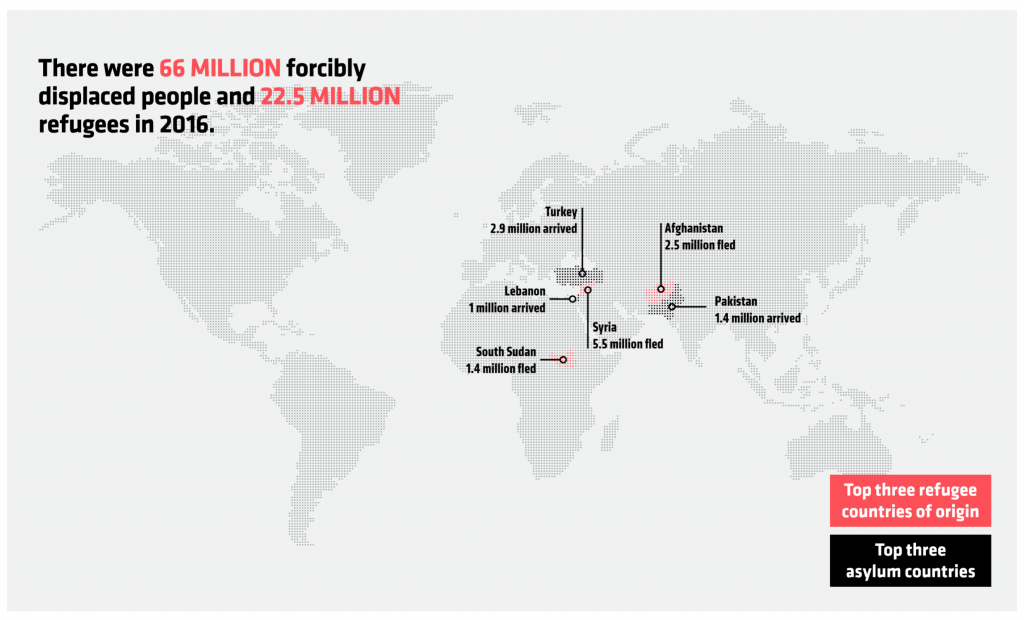

Meanwhile, manmade disasters affected nearly three times as many people last year. The latest figures from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reveal that 65.6 million people were forcibly displaced from violence, conflict and persecution worldwide in 2016. Over a third of those people fled across international borders. “War, violence and persecution have uprooted more men, women and children around the world than at any time in the seven-decade history of UNHCR,” the agency’s website says. “On average, 20 people were driven from their homes every minute last year, or one every three seconds.”

There is not much that any one actor or organization can do to address the roots of disaster, natural or manmade. But a growing number of industry players are stepping up to try to ease the discomfort of displaced people, and ultimately help them rebuild their lives long-term. Swedish furniture giant, IKEA is one of them.

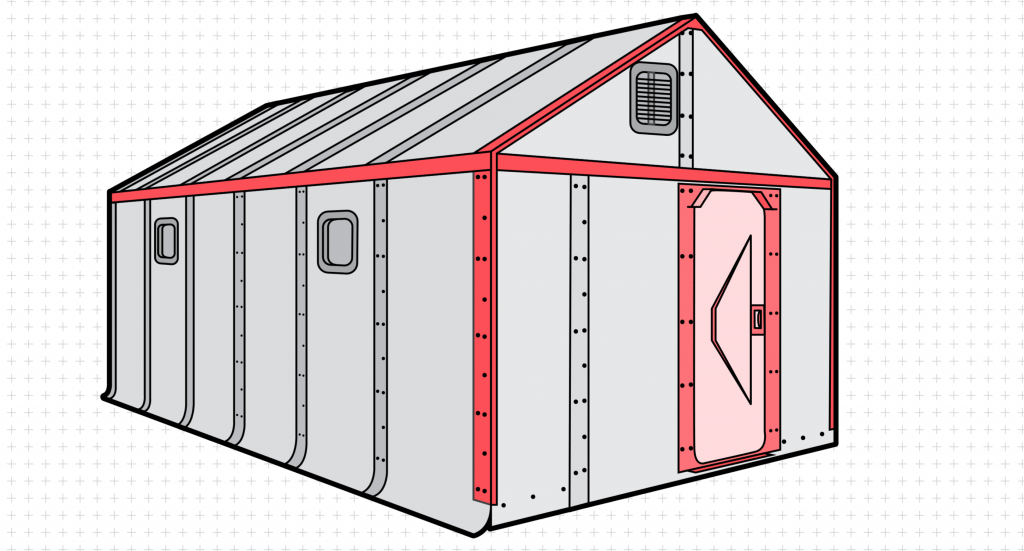

Recognizing that many displaced people are forced into temporary shelters, IKEA set out in 2010 to develop something more secure, comfortable, and structurally-sound than the tents and other cheap housing options most relief organizations use. “Even the strongest tent will only last a matter of months,” an IKEA corporate statement says. “Refugees often spend several years—even generations—in camps.”

IKEA backed the launch of Better Shelter, a social enterprise tied to the company’s foundation that develops and provides housing solutions for displaced people. The startup is driven by “the belief that sustainable design can make a difference to humanitarian relief.”

In partnership with UNHCR, Better Shelter developed a steel-framed, 17.5-square-meter modular housing unit that, like other IKEA products, comes flat-packed and can be assembled by pretty much anyone. Each unit comes with its own assembly tools and includes a lockable door for security and privacy, a small rooftop solar panel that powers an LED ceiling lamp, lightweight insulated polymer panel walls for warmth, and windows and ventilation openings for circulation. Each unit costs US$1,150 and is built to last for up to three years housing a family of five.

“The upfront price is double that of an emergency tent [but] the solution is still more cost effective considering its longevity,” Johan Karlsson, Better Shelter’s head of business development said in an interview with The Borgen Project, a non-profit focused on poverty alleviation. Better Shelter’s goal is to get the cost below $1000.

The startup will have some time to work on that before its product becomes widely available. It piloted the shelters with refugees in Ethiopia and Iraq in 2014. The following year, UNHCR committed to buying and deploying 15,000 units. But issues with the design have since come to light and UNHCR has halted its rollout of the structures at 5,000 units while Better Shelter goes back to the design studio. Among the criticisms: weak framing, poor ventilation, lack of wheelchair access, and fire safety concerns.

Responding to the fire safety criticism, Tapio Vahtola, UNHCR’s head of strategic partnerships, told design magazine Dezeen that the Better Shelter was built to be “fire retardant, but as with any other building or tent, it will not withstand flames from an uncontrolled fire.”

From Vahtola’s organization’s standpoint, managing fire risk in crowded settlements like refugee camps comes largely down to planning. “We are introducing guidelines in order to improve the safety distance between units in camp settings and to minimize the risk of fire spreading between shelters in the case of a fire starting in a settlement,” he said.

Better Shelter is planning a new release of its product later this year, according to design publication inhabitat. Improvements in the works include a more rigid frame and wall panels, built with lighter yet tougher materials; better ventilation and lighting; and an upgraded solar panel.

While the redesign may seem like a setback for both Better Shelter and UNHCR, Vahtola says it is not unusual for the innovation process to take turns and detours. “The very nature of innovation and new product development implies improvements are required along the road—iterations based on experience, on end-user engagement, and on robust data, but underlined by a commitment to try to constantly improve,” he was quoted as saying in Dezeen.

He added: “I believe that it is important that UNHCR continues to challenge itself, and the partners it is fortunate enough to work with, to constantly improve the products, services and process[es] we employ to provide refugees with protection and assistance, and ultimately, to help them to live more dignified lives.”

As for IKEA, the company’s commitment to alleviating the global refugee crisis goes beyond its product line. Jesper Brodin, IKEA’s head of range and supply told Dezeen that the company feels it has a responsibility to “not only help refugees and other people with severe needs, but [to] actually accelerate them into society.” Reflecting that sense of responsibility, IKEA announced plans to employ 200,000 “disadvantaged” people through social entrepreneurship programs, starting with refugees in Jordan.

“If you want to change the world, you have to be able to scale ideas,” Brodin added. “If you want to scale ideas to create good, you need to have the big companies with you. I think today there is a broad understanding that that needs to happen.”

Following suit

Cisco, GE, and IKEA each found a niche developing products and services in underserved markets earlier than most. Now, other industry giants are following suit. Many are spurred by their own market ambitions, while more yet are responding to growing pressure and momentum from the global community to tackle pressing challenges within the framework of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 and the Paris agreement on climate change.

Both frameworks will take trillions of dollars of investment each year to meet their targets, but they represent a larger market opportunity, according to the Better Business, Better World report, released this year. For example, achieving the Sustainable Development Goals alone “opens up $12 trillion of market opportunities [in] food and agriculture, cities, energy and materials, and health and well-being [representing] around 60 percent of the real economy,” the report says.

It continues: “Business leaders need to strike out in new directions to embrace more sustainable and inclusive economic models. Business as usual is not an option.”

Editor’s note: A version of this article appeared in the Summer 2016 edition of Demand: ASME Global Development Review.

Molle Bloudoff-Indelicato is a journalist covering science, health and the environment. She is a former editor of Everyday Health and has reported for NPR, National Geographic, Nature Medicine, E&E Publishing and Scientific American. Mollie holds a master’s in journalism from Columbia University in New York.

Jessica Pothering is a business journalist focusing on social innovation, finance and economic development. Her reporting and research topics range from social impact bonds in the United States to social entrepreneurs in Southern Africa. She is Demand’s managing editor.

Amazing