India has the world’s highest water-borne illness mortality rate with nearly 160 million people in the country lacking access to safe and reliable water. Although Household Water Treatment and Safe Storage (HWTS) has proven to be an effective water treatment method, it has not been promoted or encouraged HWTS in the country via any policy or programming. India’s current water supply strategy focuses on community-based treatment solutions, which are managed at the state level. Within the private sector for moderate- to high-income households, there exists a developed market of water treatment technologies, with reverse osmosis, UV, filtration, and chemical purifiers being widely used. For low-income households and rural areas, technologies such as Biosand Filters, ceramic filters, chlorine systems, and SODIS are sometimes present. However, the distribution of HWTS in rural communities is largely through NGOs, SHGs, and microfinancing; much different from the urban market-based approach. Overall, the potential for reducing waterborne illness through the accessible and low-cost household water treatment technologies in rural India is vast.

Country Statistics

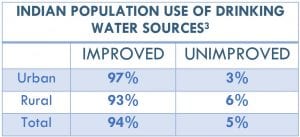

India is one of the most densely populated countries in the world with nearly  70% of the country living in rural communities. Although 50% of India’s urban population has access to piped water supply (PWS), almost 90% of rural populations still rely on pumped groundwater for their daily needs. With 42% of rural water supplies known to be heavily contaminated, the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS)1 aimed to increase rural access to treated piped water by 2017 but failed to meet this goal due to an apparent lack of interest from both central and state governments in working in the rural sector.2 According to the JMP, 94% of the country has access to improve water supply sources,3 however, India remains to have the highest rate of water-borne illness deaths in the world due to the fact that an “improved” water source may not necessarily be safe. Sources such as untreated tap water, hand pumps, and bore/tube wells are all included in the definition of improved water sources but can be easily contaminated during collection and distribution.

70% of the country living in rural communities. Although 50% of India’s urban population has access to piped water supply (PWS), almost 90% of rural populations still rely on pumped groundwater for their daily needs. With 42% of rural water supplies known to be heavily contaminated, the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation (MDWS)1 aimed to increase rural access to treated piped water by 2017 but failed to meet this goal due to an apparent lack of interest from both central and state governments in working in the rural sector.2 According to the JMP, 94% of the country has access to improve water supply sources,3 however, India remains to have the highest rate of water-borne illness deaths in the world due to the fact that an “improved” water source may not necessarily be safe. Sources such as untreated tap water, hand pumps, and bore/tube wells are all included in the definition of improved water sources but can be easily contaminated during collection and distribution.

Government Policies for HWTS

Although the Indian government has well established drinking water standards4 and acknowledged the importance of HWTS as the most effective and cost-efficient means to prevent water borne diseases,5 there is minimal focus on it.6 The MDWS is the central governing body for national water affairs while local water supply is managed by each state. In 2013, the National Environment Engineering Research Institute (CSIR-NEERI) and MDWS issued the Handbook on Drinking Water Treatment Technologies recommending community- and household-level water quality interventions. Among HWTS, the manual endorses solar disinfection, chlorination, ceramic filters, combined flocculation/disinfection, and boiling. In the 2015-16 Annual Report, the MDWS announced the creation of the International Centre for Drinking Water Quality (ICDWQ) to support the nation’s water-related issues, with a focus on arsenic and fluoride contaminants. In 2015, MDWS also released the Compendium of Innovative Technologies on Rural Drinking Water and Sanitation, which included minimal discussion of HWTS, mentioning only Aqua+ WATA Technology and P&G purification packets. Additionally, in 2015 the Ministry convened a workshop for the National Accreditation Board of Laboratories (NABL) for water quality testing and certification, but again focused on community-based systems.

HWTS in the Private Sector

The market for HWTS in India has high demand among moderate- to high-income households but is lacking among low-income households.6 Products such as Pureit, Kent, Aquagaurd, and Tata Swach, which have been accredited to meet WHO and US-EPA drinking water standards, are available for higher-income households. However, there is a significant deficiency of HWTS products marketed towards the “bottom of the pyramid” with only a small fraction of rural households using household filters or boiling water over cookstoves. Creating demand through affordable low-cost HWTS product promotions, awareness campaigns, and connecting with consumers through microfinance opportunities are some effective ways for market expansion in these sectors. Across India, self-help groups (SHGs) are established to provide a social network around community-based concerns. These groups can be used to promote adoption and sustained use of HWTS though social awareness programs and microfinancing.7

There are a great number of NGOs working to provide safe water solutions in rural India including Parinaam, which distributes Pureit water filters via interest-free loans, and Development Alternatives, which distributes household-level SODIS and promotes HWTS in rural communities and urban slums. Additionally, there has been a strong network of Biosand Filter distribution by organizations such as South Asia Pure Water Initiative, Assembly of God Church Kolkata, DHAN foundation, and Sehgal Foundation.

Examples of HWTS in India

Arogya Water Filters

Biosand Filters

TATA Swach Cristella Plus Water Filter

TATA Swach Smart

P&G Purifier of Water

Zimba Automatic Chlorine Dispenser

Ceramic Filters (flower pot style)

Solar disinfection (SODIS) using plastic bottles

Boiling over cookstoves

Tabletop filters for As, Fe and F removal by Bhartiwaters

Challenges

Providing affordable and accessible HWTS presents a variety of challenges in India. Notably, there seems to be a lack of awareness of the importance of water quality in rural communities. Additionally, financial constraints, inequity across classes, and unavailability of affordable solutions play key roles in low adoption rates of HWTS in low-income households across the country. Investing in affordable HWTS technologies, encouraging public-private partnerships, and utilizing microfinance institutions can play crucial roles in improving access to safe water in low-income and rural households in India.

References

- MDWS 2011-2022 Strategic Plan

- Sengupta, S., Mahapatra, R. “To meet 2017 target, one million rural households need to be connected with piped water supply every day.” DownToEarth. Updated: 30 October 2017.

- JMP Report 2015

- Indian Standards for Drinking Water, IS 10500: 2012

- MDWS, “Handbook on Drinking Water Treatment Technologies, 2nd Edition.” February 2013

- PATH, Supply and Demand for Household Water Treatment Products in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Maharashtra, India

- Freeman, M.C, et al. “Promoting Household Water Treatment through Women’s Self Help Groups in Rural India: Assessing Impact on Drinking Water Quality and Equity.” PLOS ONE, September 2012, vol. 7(9).

No Comments.